Bri (she/her) smiles from behind an acceptance letter to the Artist Wilderness Connection program for summer 2023.

This summer has whirled by, leaving many a drafted blog post unfinished — including an announcement of a thing that has now been completed. Since my intermittent writing here is no indication of my excitement around the experience, I’m coming back to edit and share now: I was selected as Artist in Residence for the AWC collaborative program supported by the Bob Marshall Wilderness Foundation, Swan Valley Connections, Flathead National Forest and Hockaday Museum of Art.

For a few years I’ve been seeking an artist residency embedded in nature. It took many an adjustment to internal dialogue and friendly artist meeting to convince myself of being a worthwhile applicant. Then a whirlwind of life full of reckoning, grief, loving and exhaustive healing made it a necessity. I’ll attempt to spare details here to surmise: adjusting from what can be simplified as a compulsory heteronormative life to one with space for queerness has not been simple, easy, or bright. While it has reaffirmed relationships that hold the most importance for me, none have remained untouched or otherwise avoided being redefined in some way. Growing pains is an understatement. I am so proud of how navigating this shift with love, radical honesty, curiosity, and unconventional relational dynamics has played out with those willing to share in approach — particularly the shift between husband to a new role that lacks appropriate terminology; something along the lines of a best friend connected in karass-like ways, to borrow a phrase from Vonnegut. All that said, it’s been exhausting and resulted in a level of heart and head-fog I have no business sorting on my own, left to what little devices I have. And no space I’ve held has been without complication.

Self In Process (winter 2022-2023) was the first time Bri returned to self portraiture since undergraduate studio time.

Spending time between spaces curated by past selves and spaces of others compounded feelings of disconnection to place for me. Inhabiting new physical spaces while attempting a full investigation of identity and lost sense of self — at least versions of self I’d defined for myself through my life until this point — has been disorienting to say the least. When in Maine, I was surrounded by memories of a happy life that no longer fit, relationships irreparably broken, others renewed, and multitudes of missed expectations; no choreography number could dance around emotional minefields without stepping in a few on even the shortest track. In Montana, I found myself inhabiting spaces defined and designed by others, living from bags and making small attempts at grounding that ultimately were ineffectual, and attempting to connect with people who had no memories of me, and also lacked the closeness that trust and knowing provides in familiar relationship — things I needed while actively falling apart. Most spaces were incredibly lonely, no matter where I found myself. Every sense of “home” as informed by a space outside of myself was lost. With so much of my life up in the air, I craved spaces I knew and who knew me in my fullness. Most of these spaces existed beyond human curation, deep in nature. And here I was, 3,000mi away from the familiar streams, brooks, and rivers that had guided me back to myself. I needed to create connections in the natural spaces around me, and finding a nature-based artist residency program seemed like an opportunity to do so with curious, open presence guiding the way.

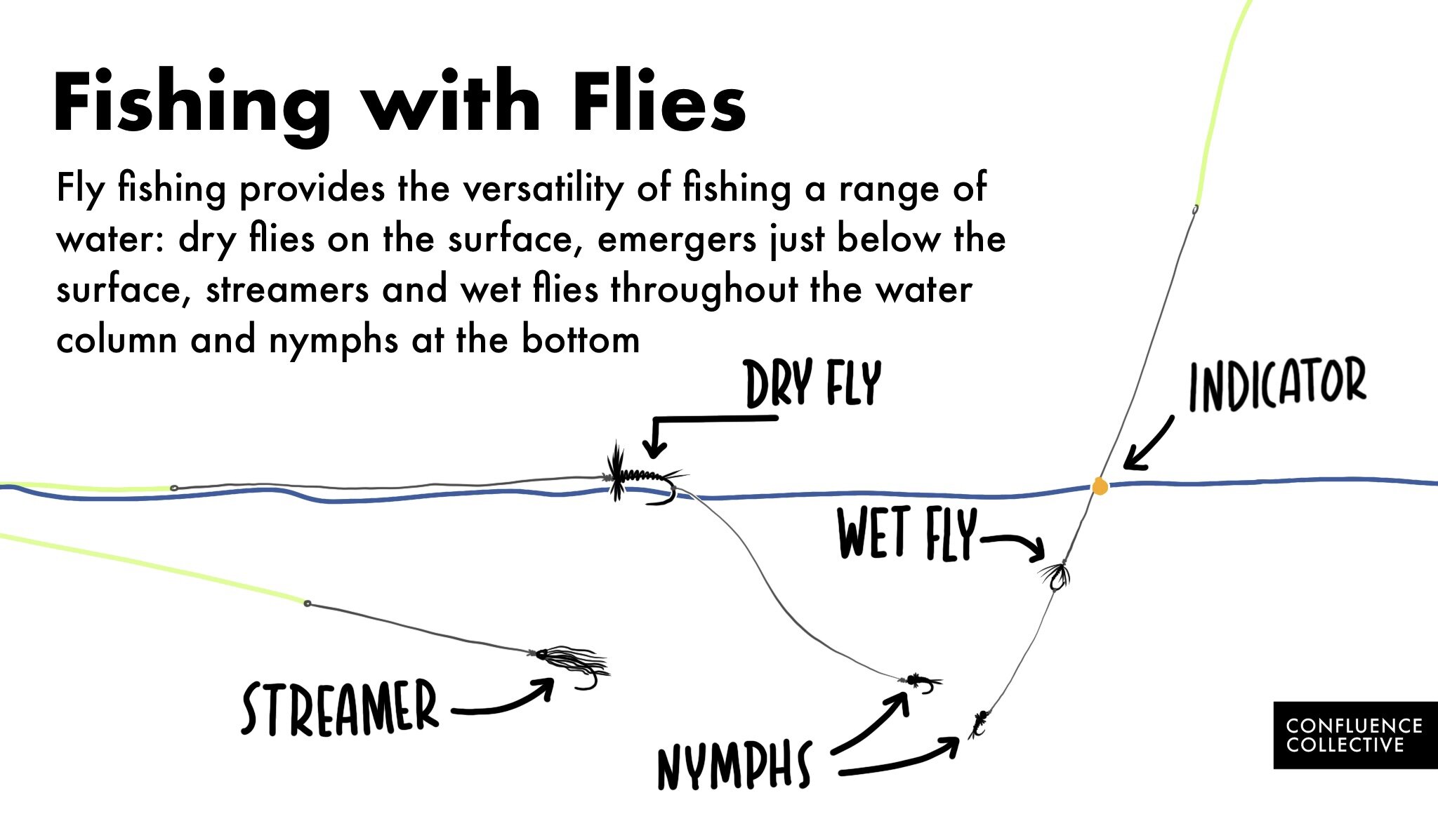

In the early exciting, optimistic, and hopeful days of reconnecting with myself in a more embodied and honest (very queer) way, I was spending my time in new waters throughout Montana for work and for fun. I felt enlivened by the dramatic and uncompromising scenery, and strangely entangled early on as fishing skills translated readily to fish encounters. I was building back confidence in self, love of self, and wanted more canvas to draw out the life I could inhabit. One such place I was introduced to was the north fork of the Blackfoot river, on the edge of the Bob Marshall Wilderness.

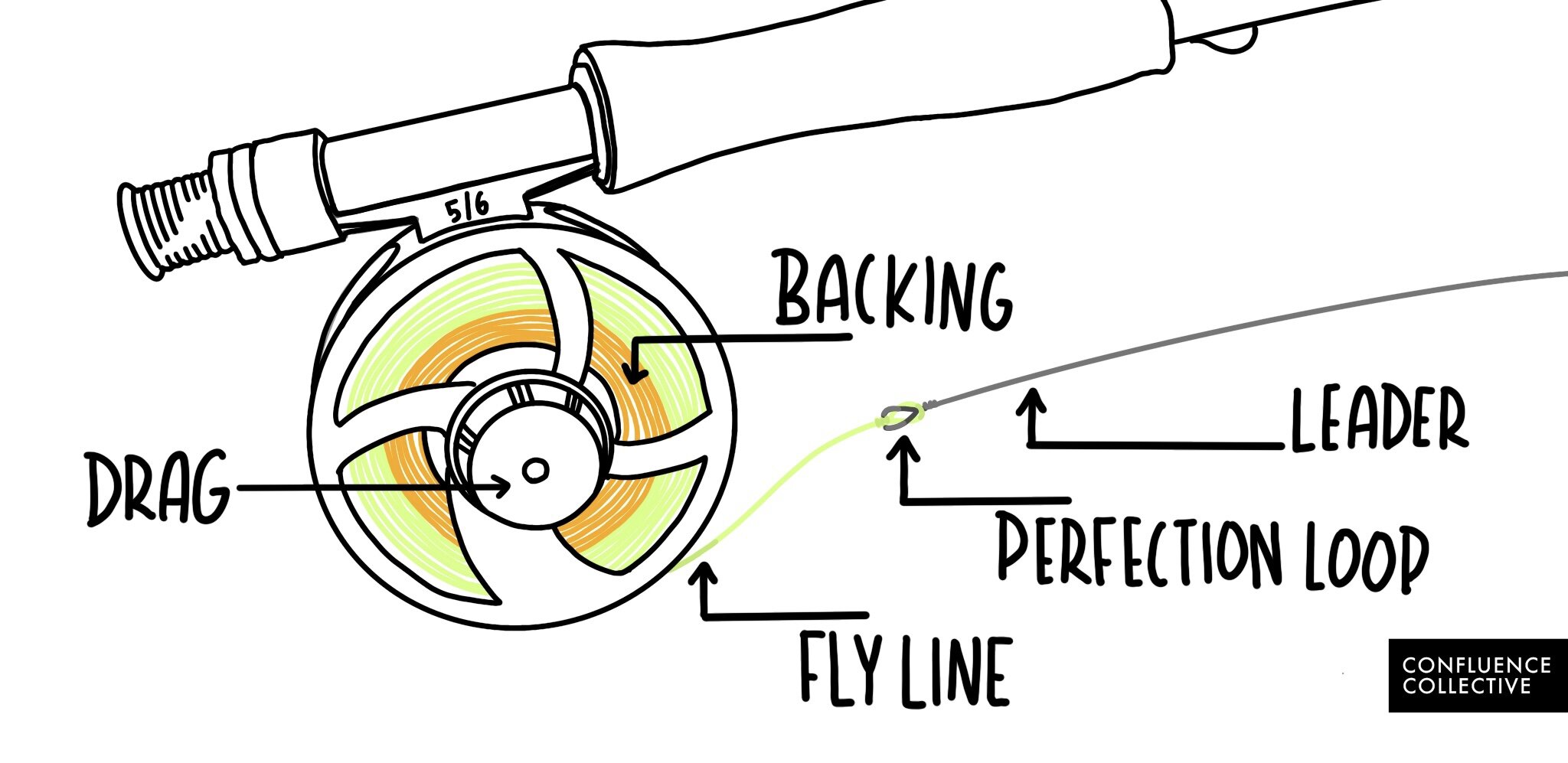

Bri heard about The Bob after the first Confluence Collective Outcast Campout, initially attempting to catch cutthroat trout on size 20-something dries with 16’ leaders. This all took place after a formative experience in Yellowstone, backpacking with friends Gabaccia and Ileana before making their way to Montana.

Here, casting to feeding cutthroat trout in crystal clear water, I felt myself reconnect with nerves and tendons, remembering the motions, and applying what I knew of myself to tease out new discoveries. Mending line over gentle cross-currents; pausing between fly changes to squat and marvel over rocks of red, purple, green, mustard, and turquoise; rummaging through riverbank undergrowth for ripe thimbleberries. I felt the filters I’d placed over myself lift, and a bubbling of unmitigated self overflowed. In these places, I returned to myself in ways I simply could not outside of nature.

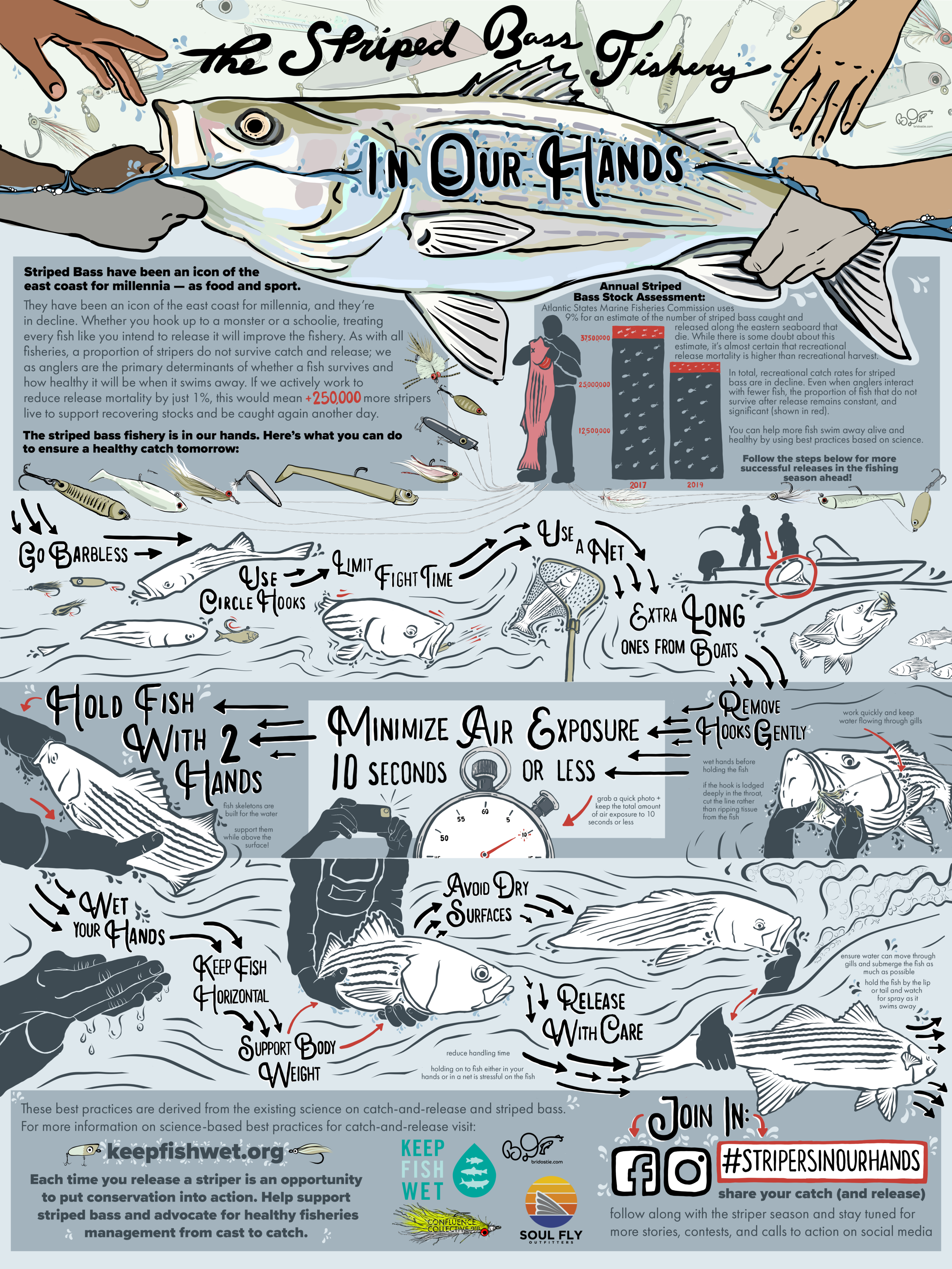

Fast forward through months of heartbreak, reckoning, and general emotional chaos, I knew being close to the water would provide the emotional and physical balm I craved; since no childhood blanket could wrap me tight enough these days to weather the storm, giving in to the inherent shifting nature of ecosystems carved by water felt more comforting as waves of emotion and sensation carved new currents through my bones. The familiarity of a current held many reminders of how natural a process I was experiencing and navigating, even when socially others challenged, avoided, or full on rejected unfamiliar dynamics I was establishing (spare a few core humans, xoxo). And so many more nature-spirit connections no text here can express in adequate depth…all of these were lighting a fire under me to find ways to be outside, far from human-curation. A wilderness began to sound downright homey.

view of a distracted angler, excitedly looking at westslope pebbles and rocks while not catching fish

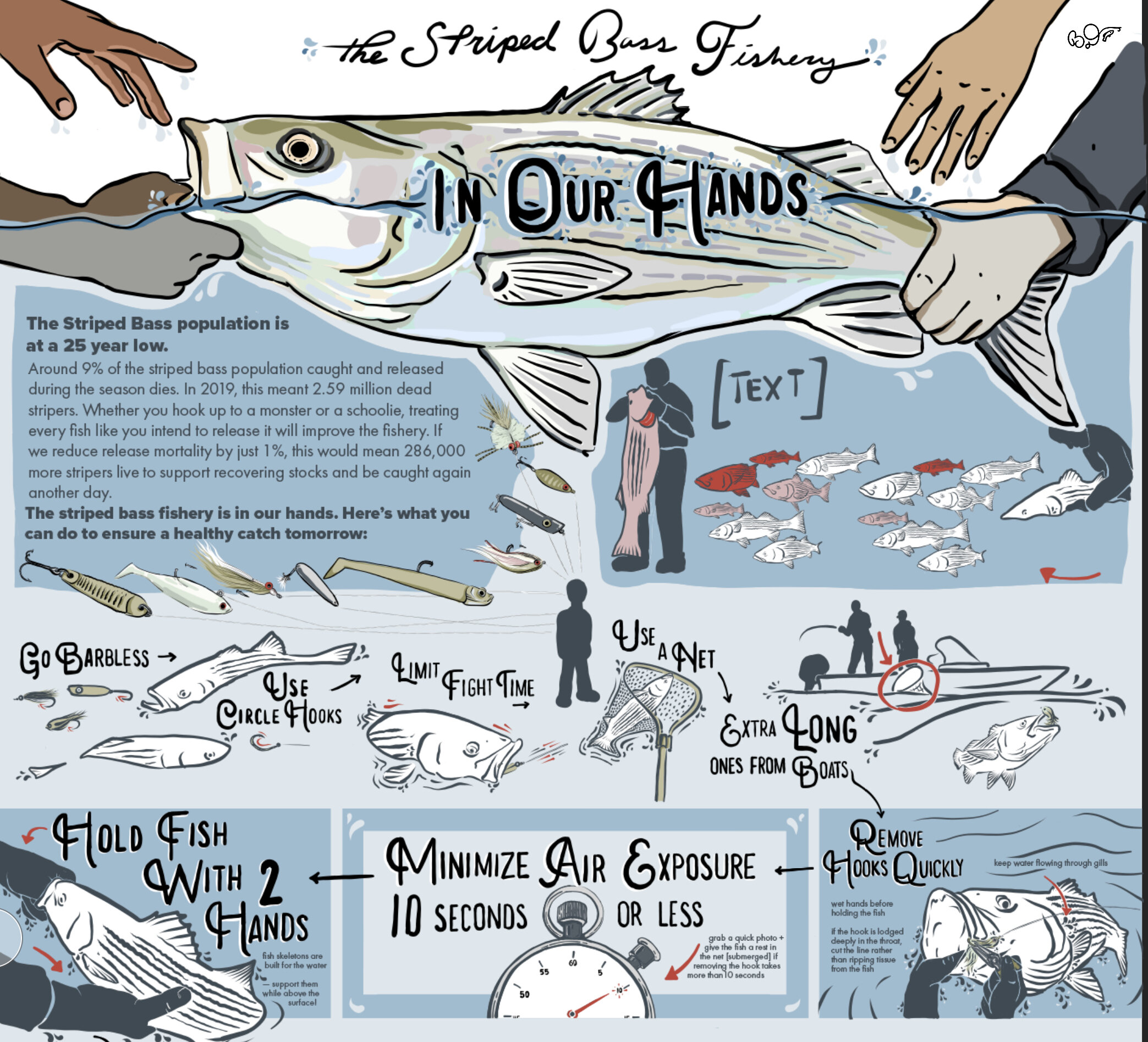

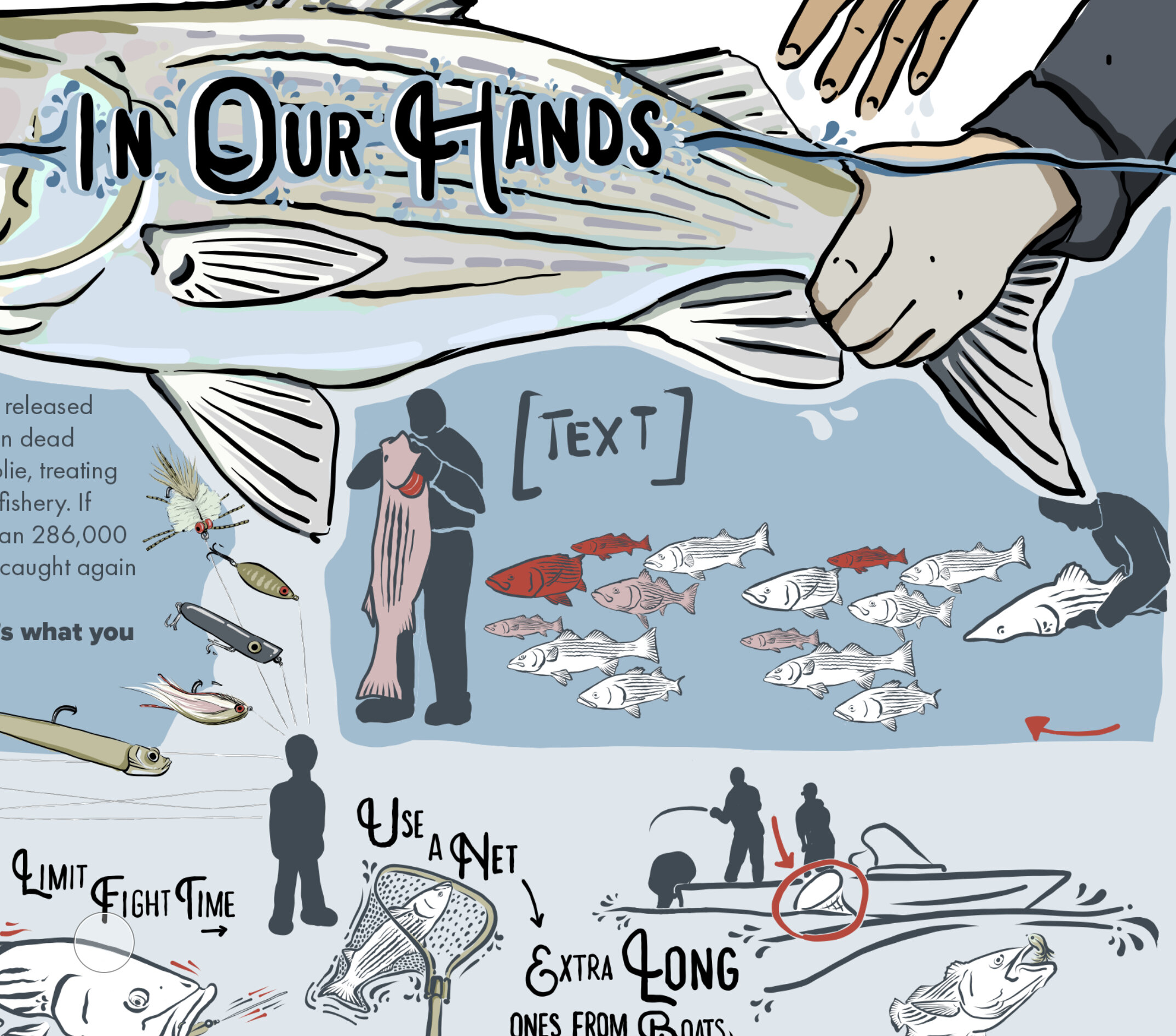

In early August, right in the middle of busy programming season and on the tassels of a massive completed scientific illustration project (more on that to come!) I found myself at the Hungry Horse Ranger Station. I had driven the 2+ hours from Missoula and met with a conference room table full of people, all supporting a program that only 2 humans participate in annually. Faces connected to email signatures, Forest Service radio communication expectations were set, the term “untrammeled” was thrown about, maps were spread out and trails traced by excited fingers of those who knew them firsthand. I had selected a site within the Bob Marshall, known for prolific grizzly populations as a rule, but the little corner of the Flathead I would find myself on for two weeks is home to the highest concentration in the whole wilderness complex. Cool cool cool. I listened intently as biologists shared encounter recommendations and stories from the field. I asked about less-than-friendly human encounters, and felt less-than-assured. Regardless of all details, I would find myself at the trailhead a few weeks later to build relationship with new-to-me waters in the Great Bear Wilderness.

From left to right: Bruce, Bri, Mark, Herb and the pack team prepare to hit the trail at the start of the AWC experience. Artists in this experience are supported by pack teams to help bring in materials, supplies, and gear to remote administrative cabin placements in the backcountry.

In what became known as typical moody fashion, the middle fork of the Flathead meanders through canyon in foggy trappings and rainy skies.

The privilege of this experience is not lost on me; in no world I define as reality would I be able to hire a pack team to take in supplies to a backcountry cabin for a few weeks that is otherwise closed to public use. I, like many, have a hard time shutting off work-wise: out of office messages are few and far between, and my inbox suffers as a result. Nor can I set aside time in my freelance schedule to not work towards some kind of income without feeling it. While the bandaid of evening fishing adventures and weekends outside maintained some level of normalcy in my nervous system this year, I wouldn’t describe it as rejuvenating or restful — nor would I describe my “normal” as working for me anymore. In a life season of overhaul, committing to two weeks in the backcountry in near solitude sounded like a more effective prescription, and one I had been needing. The guide in me could bolster my confidence in my capabilities. The child in me could get revel in the lack of time limits for picking through rocks on the riverbank. The angler in me could be excited to meet fish where they’ve lived for thousands of years, without the pang of more concentrated fishing pressure or regular human encounters stressing them. The forager and birder in me could look and listen with attention to mosses, trees, and conditions I’d only just begun recognizing. As preparations continued, more and more parts of self showed up with enthusiasm.

evening light fades on the Granite USFS Administrative Cabin I called home during my residency, perched atop a red and green rock overlooking the middle fork and surrounded by thick vegetation.

signs from past visitors to the cabin in the form of claw marks and tufts of fur left behind as a message to others inhabiting the community.

I have so much more to still process of the experience, which will require more time. For now, I do want to share a few images from my time as glimpses of what is occupying my attention, artistic/creative and otherwise. I find myself sitting with feelings of humble grace for this body I inhabit, in humility to my small role in this world, in gratitude for those supporting me and encouraging me to show up authentically and completely, and in continued currents of change I will continue learning and moving through. I am renewed in my efforts to facilitate relationship building with the water, as I continue to benefit from my ongoing entanglements with rivers, streams, oceans, and still water every time I return to them. I am here in many ways, because of them.

a deep pool is touched by early light, dancing on the riffles and sparkling with every slow eat from hungry cutthroat trout.

an angler’s view of the middle fork of the flathead as seen on foot, wading towards the next pool…and the next…

a healthy and relatively unbothered westslope cutthroat trout swims back to the safety of a deep pool after brief encounter by way of dry fly

up close and personal with the rocks of the region, full of deep red tones and surprising shapes and forms

one of the many butterflies animating the shorelines as they bounce between late-summer blooms

a closer look at the dense vegetation climbing up from the water to dense coniferous forest

a colored-up cutthroat breaks the surface of the water as it swims away from the riverbank

Allowing for some emergent practice, I’ll walk away from this post now and return with more rumination guiding my typing fingers. In the coming weeks of autumn, I anticipate more artwork (beyond what my mirrorless camera could support) to fill the page, and more digested stories to sift through the newness of it all. Not to spoil any surprises, but I’ve got some work to do on getting my guts back in functioning shape, and mind back in assured state. I am learning to care for myself in ways that have been needed for so long. Thanks for being around for the journey here!

Bri